What is Legg - Calve Perthes Disease

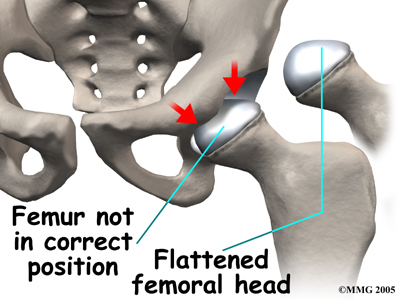

Perthes disease affects the hip joint. The hip joint is a ball and socket joint, the ball is the femoral head and the socket or cup is the acetabulum. Perthes disease causes avascular necrosis of the femoral head. This means that the blood supply to the femoral head is disrupted causing some of the bone to die. As part of the body's normal healing process, the body breaks down this dead bone before new bone is made. But the resorption of this dead bone leads to structural weakness causing collapse and deformity.

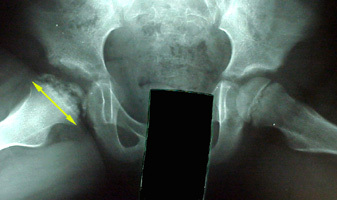

Perthes disease can be broken up into stages. The first stage is the loss of blood flow to the head of the femur, causing it to die totally or in part. The dead bone is still structurally sound, but to the body, it is foreign tissue. The body then absorbs the dead material in a Swiss cheese-like pattern. Structural weakness results, and the outer surface of the femoral head may collapse in. Depending on the location of the resulting "soft spot", it may be more or less a problem. If the original dead bone was extensive, the removal of tissue and subsequent collapse will yield a mushroom-shaped, widened and flattened femoral head (see x-ray above). This collapsed head no longer matches with the socket, and the last step will be the shape adjustment of the socket itself to the altered femoral head. A consequence of this change in shape is that movement in one direction may be quite good, but movement in another direction may be absent. A common outcome is the ability to flex and extend the hip, but not rotate it.

Perthes disease can be broken up into stages. The first stage is the loss of blood flow to the head of the femur, causing it to die totally or in part. The dead bone is still structurally sound, but to the body, it is foreign tissue. The body then absorbs the dead material in a Swiss cheese-like pattern. Structural weakness results, and the outer surface of the femoral head may collapse in. Depending on the location of the resulting "soft spot", it may be more or less a problem. If the original dead bone was extensive, the removal of tissue and subsequent collapse will yield a mushroom-shaped, widened and flattened femoral head (see x-ray above). This collapsed head no longer matches with the socket, and the last step will be the shape adjustment of the socket itself to the altered femoral head. A consequence of this change in shape is that movement in one direction may be quite good, but movement in another direction may be absent. A common outcome is the ability to flex and extend the hip, but not rotate it.

A Perthes hip will not have the natural longevity of a spherical normal hip. Early onset degenerative arthritis is common.

The role of treatment is to try to maintain the spherical shape of the femoral head.

The etiology of Perthes disease is unknown but there are many theories. The most promising theories center on the blood clotting mechanism. Many children with Perthes have low concentration of certain blood factors, which help break up clots. These children clot their blood too easily. They may develop a clot in the few small blood vessels, which are vital to the blood supply of the femoral head leading to avascular necrosis. Another link is to passive smoke inhalation. Certain drugs such as steroids and amphetamines can also cause avascular hips. Trauma and prior hip synovitis has been suspected as well. There may be multiple factors in something as general as impaired blood supply.

Children will generally first complain of hip pain and limp. They may have decreased range of motion of the hip, especially rotation. An x-ray of the hips will often pick up changes in the femoral head that signify Perthes disease. Sometimes the changes are too subtle to see on x-ray. In these cases, MRI and bone scan are able to pick up these changes and lead to the diagnosis.

The time of diagnosis is important for the prognosis of the disease. When the diagnosis is made before the child is six years old the prognosis is better. Younger children have better remodeling potential. Treatment is more likely to prevent deformity in the younger child.

The amount of the femoral head involved is also important. The greater extent of femoral head involvement, the worse the prognosis, especially if more than half the femoral head is involved. There are many classification systems devised to describe the involvement of the femoral head. The most used classification system focuses on the outer column of the femoral head. The more normalcy maintained here (closest to the cup edge), the better the prognosis.

Treatment of Perthes disease centers on one main concept, containment. Containment means keeping the softened part of the femoral head within the acetabulum (socket) so the acetabulum can act as a round mold and help keep the femoral head round. This can be accomplished many different ways.

Who requires containment treatment? A simple rule to remember is "half a dozen, half a head". So, if the patient is greater than six years old or has more than half the femoral head involved containment, treatment should be considered.

Maintaining hip motion is very important. A joint requires full motion to develop properly, as if forming clay on a wheel. If motion is lacking then abnormal focal pressure is placed on the hip (especially by the cup edge) leading to deformity. Children with early Perthes (before femoral head deformity) are started on range of motion exercises. If muscle tightness is apparent then a muscle lengthening is performed to increase hip range of motion free of compressing restraint. Tightness most commonly occurs in the hip adductor muscles.

Maintaining hip motion is very important. A joint requires full motion to develop properly, as if forming clay on a wheel. If motion is lacking then abnormal focal pressure is placed on the hip (especially by the cup edge) leading to deformity. Children with early Perthes (before femoral head deformity) are started on range of motion exercises. If muscle tightness is apparent then a muscle lengthening is performed to increase hip range of motion free of compressing restraint. Tightness most commonly occurs in the hip adductor muscles.

Braces have been a mainstay of Perthes treatment for some time. Recently, using braces has been falling out of favor, as some studies have been done which question their effectiveness. A brace aims to hold the hip in an abducted (out to the side) position, which places the outer portion of the femoral head (the part most at risk) deeper in the round acetabulum. Hopefully, this will help the femoral head remodel as the disease runs its course. Some institutions are moving away from using the brace at all in light of the new research. The braces are sometimes worn for two or more years because that how long the hip will take to fully remodel.

Once the head is deformed, surgical forms of containment are considered. The main procedures described for treatment include proximal femoral osteotomy (cutting the proximal femur and aligning it to place the femoral head deeper in the acetabulum), pelvic osteotomy (reorienting the acetabulum to better cover the femoral head), and a shelf procedure ("acetabuloplasty"), making the acetabulum bigger to accommodate the deformed femoral head). Each procedure has its advantages and disadvantages.

An important thing to remember is that the hip affected by Perthes disease will not be a normal hip. The goal is to alter the natural history of the disease. With treatment, the physician wants to keep the hip pain free, allow the child to participate in all activities, and prevent the development of early hip degenerative arthritis.

From: Pediatric Orthodedics

Updated February 13, 2009